In the coming decade we can expect an acceleration in new Gene Therapies against devastating diseases; and that is fantastic news! Gene Therapies should be relentlessly pursued until the burden of all genetic disease is a thing of the past. I am grateful for society’s investment into those of us fortunate enough to practice innovative science to deliver nothing short of a miracle with Gene Therapies.

While Gene Therapies do contribute to incredibly positive and measurable health outcomes, they are not supernatural miracle cures. The benefits of Gene Therapies, and the associated value of those benefits, can be perceived very differently by various stakeholders; mainly patients, payers, and drug developers. Clarity on “how much” and “what for” the customers are willing to pay defines the incentives for suppliers to deliver on.

Are the high prices for Gene Therapies based on their miraculous health benefits, or something else entirely?

The most influential and empathetic justification for the high price of gene therapies is the value that they bring to patients and society. It is absolutely true that ultra-rare genetic diseases can be devastating to patients, many who are children. The emotional burden to families and financial burden to healthcare systems may be incalculable. Nevertheless systematic attempts for pricing new therapies are evolving.

The most accepted method for pricing therapies is “Value Based Pricing” through evaluation of cost effectiveness. Cost effectiveness is determining if the overall value of benefits received minus the price paid is still greater than the alternative (living with the standard of care).

Pricing often starts by evaluating the additional Quality-Adjusted-Life-Years (QALYs) that patients experience by taking a new therapy versus the standard of care. This rationally infers that more effective therapies should be priced higher. However calculations can quickly start to get complicated

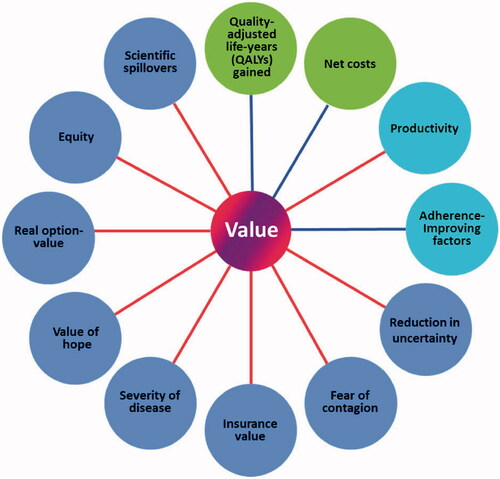

Beyond the potential health benefits for the patient, Gene therapies offer numerous benefits to families, caregivers, health care systems, and society. Anything from offsetting lost productivity, providing hope, to progressing scientific understanding can have value. The Professional Society for Health Economics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) tries to graphically classify all the additional sources of value in the ISPOR Flower. Expert arguments for and against the Value Flower can be read in, “Novel Elements of the Value Flower: Fake or Truly Novel?” [1].

Figure 1. ISPOR Value Flower

A criticism of the Value Flower is the potential equivocation of core elements (QALY and net costs) with subjective novel elements of value. From snake-oil to homeopathic remedies, selling narratives around fear, hope, and knowing is not novel to medical marketing. Shining a light on these intangible outcomes shades the contrast between true medical breakthroughs and where there is still work to be done.

ISPOR acknowledges the subjective complexity of assigning value to ancillary indirect benefits. The “concluding observation” was that while there is real value to these benefits, the inclusion into the cost of therapy is debatable.

Putting aside indirect benefits, assigning a financial price to a QALY is in of itself under significant debate. There are a variety of imperfect methods for assigning a monetary value to a year of perfectly healthy life. There are also subjective interpretations for how to discount this value based on anything from a toothache to a terminal diagnosis. Any objective take on the value of a QALY would be ignorant of the diversity in cultures, opinions, and individuals; all of who are equally mortal and susceptible countless health impairments.

The prevailing theory on the value of a QALY is the average for what a population would be willing to pay for a year of healthy life. “Willingness-to-pay” (WTP) is a measure for what a customer would be willing to pay for a product or service. The WTP for a year of healthy life, discounted and proportioned to the net health benefits of a novel therapy, sets a maximum threshold for a drug price that is perceived as being cost effective. Any price set over this threshold could be viewed as not cost effective, overvalued, and not worth prescribing (or covering by insurance).

While there is no clear consensus on what the WTP for a QALY should be, there are opinions on the topic. A piece in Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy lists several estimates and sources for the value of a QALY from both governing bodies and specific healthcare interventions [2]. The implied value per QALY ranges from a conservative $20k up to $39M! The more inflated price per QALY comes retrospectively from the observed benefits from the listed therapeutic interventions (possibly supplementing from the additional elements of value in the ISPOR flower referenced by the authors).

For Gene Therapies for ultra-rare disease, the interesting figure to dig into is the ICER consensus range of $50k-$150k for non-orphans and $175-500k for ultra-orphan. Who is ICER, and why are they at the top row of this table? Also, why are ultra-orphan QALYs more valuable than the rest?

For a small non-profit, ICER sure attracts a lot of attention from the healthcare industry. ICER uses their published value assessment framework [3] to evaluate the cost effectiveness of new therapies. In ICER’s analyses, the upper limit for cost effectiveness, based on WTP, is $150,000-per-QALY. Insurance companies and other payers increasingly reference these analyses when deciding if a proposed intervention, such a novel Gene Therapy, provides the value in health benefits that justifies its price. Drug manufacturers are increasingly pressured to defend or negotiate asking prices that are above the $150,000-per-QALY cost effectiveness thresholds evaluated by ICER. Depending on your opinion, ICER is either a valuable industry watchdog protecting against price gouging, or a misguided antihero punching above its weight.

In 2017 [4], ICER published “Modifications to the ICER value assessment framework for treatments for ultra-rare diseases”. The purpose of this document is to lay out special considerations that will be made when evaluating the cost effectiveness of therapies specifically for populations below 10,000 patients in the USA. The scope of modifications acknowledges the specific and significant challenges of developing and clinically testing new therapies for relatively few patients.

Of the numerous modifications, the point to narrow in on is section 3.2, “For these treatments ICER will adapt its analyses to provide willingness‐to‐pay threshold results for a broader range, from $50,000-per-QALY to $500,000-per-QALY”.

Increasing the upper threshold for WTP from $150,000 (for standard indications) to $500,000 would infer that new therapies for ultra-rare diseases could be priced up to 333% higher per net health benefit and still be considered cost effective to the public. Public perception, which was published here [5], of this modification spanned between welcoming and recommending ICER go even higher. Between sticker shock, limited patient access, and echoing calls to make Gene Therapies less expensive, why is it reasonable to believe the public has willingness-to-pay $500,000-per-QALY?

In 2014 (or 2015), the US Department of Health and Human Services commissioned a review of “Valuing Reducing in Fatal Illness Risks: Implications of Recent Research” [6]. The conclusions of the study and implications on US government policy was published in the 2016, “Guidelines for Regulatory Impact Analysis”[7]. The guidelines values a statistical life (VSL) at $9.6M, and therefore calculates a discounted QALY at $490,000 (round up to $500,000 for ease of use). Note, this guideline was again updated to $580,000-per-QALY in 2021, Appendix D [8].

Reapplying the conclusions from this study into the context of the significant health benefits offered by Gene Therapies for ultra-rare diseases could be misleading. WTP surveys can be significantly biased by the context in which they are delivered. Plainly written in the HHC Guideline:

“WTP should change nearly in proportion to the change in risk, as long as the risk change is small enough that WTP does not substantially limit other spending. Thus a single VSL can be used to value a range of small risk changes”.

One could logically infer that benefiting several years of healthy life is not a small risk change. Further, most of us would conclude that the costs associated with living with an ultra-rare genetic disease, or treating with a $1,000,000+ Gene Therapy, could substantially limit other spending. For these reasons, benchmarking the upper threshold of WTP for a QALY at $500,000, based on this reference point, would be inappropriate.

In 2020, ICER published an update to their “Modifications to the ICER value assessment framework for treatments for ultra-rare diseases”.[9] Among the many changes was an amendment to section 3.2 that reads “… $200,000 per QALY”. In discussion of the change, ICER states:

“Finally, presenting results for all assessments from $50,000-$200,000 per QALY and evLYG will preclude the unintended (and incorrect) inference that ICER had formalized a specific higher threshold as the acceptable cost-effectiveness ceiling for these treatments.”

ICER further reflected this upper WTP threshold of $200,000-per-QALY in their 2023 Value Assessment Framework [10]. They also now consistently apply their thresholds to both prevalent and ultra-rare diseases; while acknowledging challenges of meeting this threshold in the ultra-rare context. Whether parity in upper threshold for cost effectiveness nudges future prices for ultra-rare orphan therapies down, or therapies for more prevalent indications up, is yet to be seen.

The discussion until now has focused on the demand side of what a customer would be willing to pay for the health benefits of a novel therapy. We can all relate to having to make tough choices about where to allocate limited financial resources in a far from perfect world.

On the other side of the negotiation table is the drug developer who also has to make tough choices on how to distribute limited resources. When considering the supply side economics, an attendee at the 2017 ICER Orphan Drug Assessment and Pricing Summit, explicitly said the quiet part out loud starting at 51 minutes [11]. The woman makes an absolutely valid point: therapies that although may provide a lesser health benefit to individual patients, but cover a much larger patient population, on the whole have a stronger value to society and the drug manufacturer.

“I don’t know what threshold would really work in the rare space”

It is understandable that in Value Based Pricing, there will be a subjective WTP benchmarking cost effectiveness. And that this WTP will be influenced by a variety of factors stemming from surveying methodology or the novel petals of the ISPOR flower.

However setting cost effectiveness thresholds to meet supply side opportunity costs is not “Value Based Pricing”. Assigning a profitable premium to a year of healthy life is even further disconnected from reality than the already controversial price of a QALY. This strategy is akin to warping the problem statement to better fit an incomplete solution.

For a supplier, it can be much more cost effective to provide a mediocre product wrapped in a feel good story than one that is truly groundbreaking. As customers, one needs to be very clear on what they want as it sets the incentives for suppliers to compete toward.

There are plenty of disorders with prevalence to drive profit incentives for future innovations in genetic medicine. It’s unnecessary to exclude an entire generation of patients from experiencing the health benefits of modern medicine because they suffer from the wrong diseases. Taking advantage of an already broken healthcare system is not the sustainable solution.

There can be a more cost effective trajectory for Gene Therapies for ultra-rare diseases. Breakthrough discoveries in genetics and biology are paving the way for clearer targets and ways to correct them. Innovations in vector engineering and manufacturing are rapidly lowering the costs of supplying safe and effective therapeutic doses. Decentralized studies are lowering the risks in selecting meaningful endpoints and recruiting sufficient patients to clinically validate them. Demand side cost effectiveness and supply side financial sustainability can be brought together by putting patients before profits.